Institutional Context

It can be difficult to understand how policymaking in the European Union works. This page aims to improve public understanding of the EU AI Act’s institutional context. This summary was put together by Hadrien Pouget, an AI policy expert at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. He hopes it will help others trying to navigate the AI Act, and is happy to respond to further questions at hadrien.pouget@ceip.org.

1. Introduction

The EU AI Act (AIA) has received international attention, and many who have never before taken an interest in EU legislation are pouring over it to understand its implications. As unprecedented as the AIA is, it remains fundamentally a piece of EU legislation. Much of it is borrowed from common EU frameworks, to the extent that it cannot be properly understood without this broader context. Those unfamiliar with the EU may struggle to discern what is in fact new about the act and what is merely established EU practice, or miss important subtext.

This guide aims to provide an overview of the legislative context of the AIA, from the legislative procedure which has driven the AIA, through to compliance and enforcement mechanisms, many of which draw from existing EU practices. In this spirit, it largely stays away from analysing the content of the AIA; many such analyses already exist.

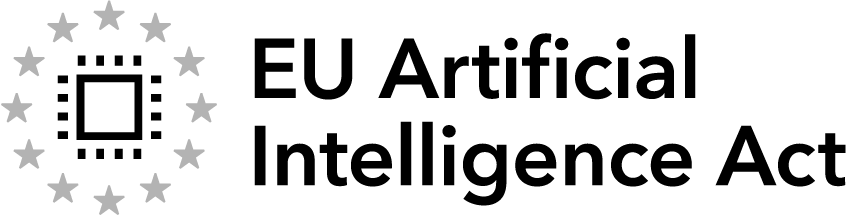

Figure 1. A summary of the most important actors in the creation and enforcement of the AI Act, and their relationships.

2. Legislative Process

The AI Act was shaped by EU’s ordinary legislative procedure, the process by which most EU legislation is produced. The key actors and their interactions are outlined here.

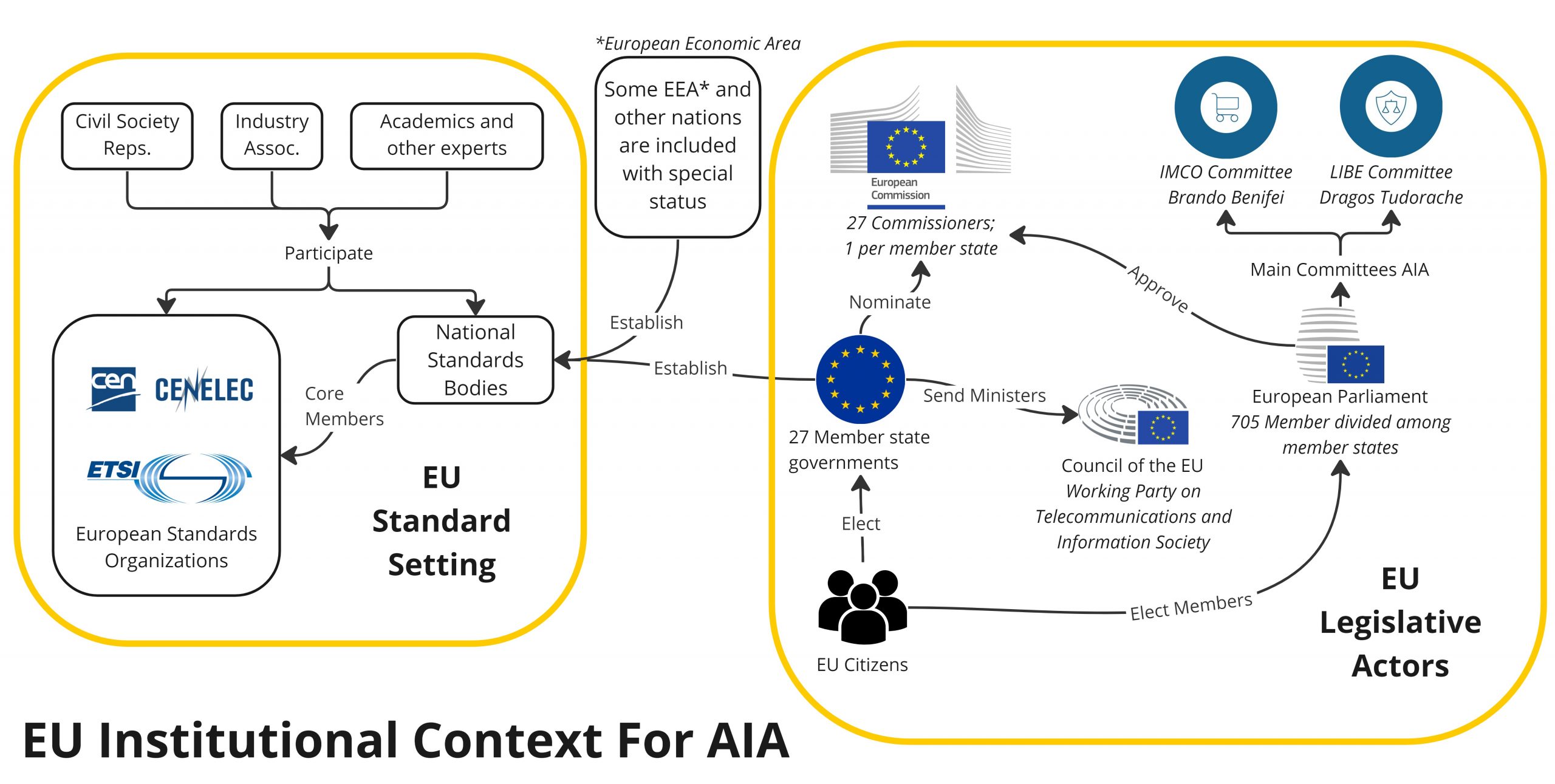

Figure 2. A high-level view of the Ordinary Legislative Procedure by which the AI Act was formed.

2.1. Key Actors

- European Commission – Composed of 27 Commissioners, put forward by member states and approved by the European Parliament. The Commission acts as the executive branch of the EU.

- European Parliament –

- Represents the people of the EU. Members of European Parliament (MEPs) are elected directly by European citizens. Each member state of the EU is allocated a number of seats depending largely on their population.

- The parliament has several committees which are expected to take the lead on issues in their jurisdiction. In the AIA’s case, these were the committees on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs (LIBE) and Internal Market and Consumer Protection (IMCO).

- For each piece of legislation, the committee has a “rapporteur,” an MEP who leads the committee’s work. In the case of the AIA, these were Dragoş Tudorache (LIBE) and Brando Benifei (IMCO), respectively. A selection of other committees were responsible for sections of the act especially relevant to their work.

- The Council of the European Union (“The Council”)[1] – For each issue, the Council convenes the relevant government ministers from each member state. The AIA was handled by telecommunications ministers under the “Working Party on Telecommunications and Information Society (WP TELECOM).” The presidency of the Council rotates on a 6-month basis between member states. The presidency has some power to set the Council’s focus and represents the Council when interacting with other EU institutions.

2.2. The Ordinary Legislative Procedure

In brief, the ordinary legislative procedure follows these steps:

- The Commission produces a first draft of a piece of legislation. It is the only organisation with the power to do so, called the “right of initiative.”

- Parliament receives the first draft and passes it back and forth with the Council, adding amendments until they agree (the legislation is passed), or until it has gone back and forth three times without agreement (the process ends and no legislation is adopted). During this time, informal dialogues, called “trilogues,” take place between the Council, Parliament, and the Commission. In practice, these are often pivotal: legislation is now usually agreed on the first pass[2], as Parliament and the Council agree on a direction through informal meetings.

- Once Parliament and the Council have officially approved the text, it is published in the Official Journal of the European Union (OJEU). The legislation will generally specify how long after its publication it will come into force.

2.3. Keeping the Act Updated After Publication

The EU has two notable tools for updating or supporting existing legislation without having to repeat the entire legislative process: implementing acts and delegated acts. Legislation must specify when these can be used, and for what purpose. The two mechanisms are similar, although implementing acts tend to focus on implementation of the act (such as by providing official guidance on compliance), while delegated acts are closer to legislative amendments, changing details written into the AI Act. Both are powers given to the Commission and include slightly different oversight mechanisms.

The AIA makes use of both mechanisms, allowing the commission to update the act in response to technological developments. They also allow the act to leave out non-essential details to be filled at a later date.

To continue bringing expertise to the EU, an AI office will be established. It will advise on some implementing and delegated acts, as well as on many other areas where expertise might be needed during implementation and enforcement.

Timeline of key developments

For a timeline of the most significant developements in the legislative process, see here.

3. Legislative Context

3.1. Types of EU Legislation

The EU can produce several kinds of legislation. The AIA is the strongest form, a regulation.

- Regulations are binding, and directly applicable in all member states.

- Directives outline binding outcomes, but do not specify how outcomes should be achieved. Member states are required to devise their own laws on how to achieve these outcomes.

- Decisions are binding and may address specific EU countries or companies.

- Recommendations and Opinions are non-binding.

3.2. New Legislative Framework – Tools for Enforcing Product Legislation

The “New Legislative Framework” (NLF), adopted in 2008, outlines the general structure that pieces of EU product legislation follow, and the tools new legislation has at its disposal.[3] It provides a large amount of boilerplate which can then be taken by new legislation and adapted. The AIA is built around this framework.

3.2.1. Essential Requirements

One of the key outcomes of EU product legislation like the AIA is a set of “essential requirements” products must meet. Once they meet these requirements, companies can access the entirety of the EU market – a large, relatively wealthy population, which serves as a tempting incentive. Essential requirements can cover anything the EU decides should be required of the product or its producer.

They intentionally avoid technical detail, instead being only specific enough to create legally binding obligations.[4] Manufacturers can then attempt to fulfil these obligations their own way, or they can use the relevant “harmonised standards.”

3.2.2. Harmonised Standards

Technical standards, produced as described in the “Standard-Setting Process” section, help make essential requirements more concrete. Once a piece of legislation is passed, technical standards are designed to address particular essential requirements. Adherence to those standards is enough to establish compliance with the relevant essential requirements as these standards carry a “presumption of conformity.”[5] Such standards are published in the Official Journal of the European Union, after which they are called “harmonised standards.”

For example, the AIA requires the adoption of “suitable risk management measures.” What counts as “suitable” is left ambiguous, and harmonised standards would bring clarity to these sorts of requirements.

In practice, harmonised standards play a crucial role. They are the most straightforward way of adhering to the essential requirements. While manufacturers may meet the essential requirements without adhering to harmonised standards, navigating the resulting grey area is often not worth it, and they must usually show their alternative solution is at least equivalent to the standard.

In cases where harmonised standards do not exist, current AIA drafts specify the Commission may create “common specifications” to compensate. These are analogous to harmonised standards, but unlike harmonised standards (developed by organisations independent of the EU), the process for developing them remains entirely in the hands of EU institutions.

3.2.3. Conformity assessments

Conformity assessments are one of the enforcement tools made available by the NLF. They must be run before a product is put on the market. If a product is found to conform to all the relevant requirements, a declaration of conformity is made, and a “CE” symbol is affixed. The product can then be put on the market.

The NLF describes different processes that conformity assessments could follow,[6] and allows for any of these three groups to run the assessment:

- The manufacturers of the product themselves. The manufacturers must of course document the assessment to prove it was run correctly. This is often the default option for lower-stakes products.

- Conformity assessment bodies. These bodies must be accredited by “notifying authorities,” which member states must put in place. Once a conformity assessment body is accredited, it is also called a “notified body.”

- Public authorities.

It is up to each piece of legislation to adapt the NLFs tools to its context – for example, the AIA may allow self-assessment for some high-risk applications, and require notified bodies for others.

3.2.4. Market Surveillance

Each member state is also responsible for market surveillance within their market; they must remove products which do not comply with EU legislation, or which do but have been found to be too dangerous regardless.

Legislation typically gives further details on how the relevant market surveillance authorities will operate. The AIA, for example, outlines what kinds of data the market surveillance authorities should have access to (documentation, datasets, source code, etc.) and under what conditions. It also outlines how the authorities should coordinate with the Commission, notified bodies, or authorities in other countries.

3.2.5. Liability

Providers of AI systems, like anyone bringing a product to the EU market, are also liable for damages caused by their defective products. While liability is not explicitly covered by the AIA, non-compliance with EU regulation makes it easier to bring a case against an organisation. The proposals for a revision of the Product Liability Directive, and for the new AI Liability Directive make this even clearer.

Notes

[1] Note that this is separate from the European Council (composed the EU member states’ heads of state), and from the Council of Europe (an international organisation entirely separate to the EU).

[2] According to the European Parliament, 89% of acts passed between 2014 and 2019 were adopted in the “first reading”. Source here.

[3] Regulation EC No 765/2008 (here), Decision No 768/2008/EC (here), and Regulation EU 2019/1020 (here) outline how market surveillance functions, how conformity assessments should be run, and how independent conformity assessment bodies become accredited. Decision No 768/2008/EC contains much of the boilerplate the AIA is built on.

[4] Points (8) and (11) in the preamble, and Article 3 of Decision No 768/2008/EC (here).