Updated: 21 July 2025.

This page aims to provide an easily accessible overview of AI safety standard setting under the EU AI Act. It covers the broader context and rationale for EU AI standard setting, the standard setting process, and questions of when AI Act standards might be finished.

This resource was first put together in 2023 by Hadrien Pouget, then AI policy expert at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. It was updated in June 2025 by Koen Holtman, standards expert at the AI Standards Lab, and Tekla Emborg, EU policy researcher at the Future of Life Institute.

Note: we focus on explaining the formal EU-based AI safety standard setting effort that is on-going in the so-called CEN-CENELEC JTC21 standards committee. Other AI standards writing efforts, like the ISO/IEC, are not covered.

Quick Summary – Standard Setting Under the AI Act

- The European Commission requested the creation of standards for the AI Act high-risk provisions already in 2021.

- Two European Standardisation Organizations (ESOs), namely CEN and CENELEC were tasked with drafting the requested standards. The drafting is ongoing and is behind schedule.

- Besides ESOs, the key players involved in the AI Act standard setting process are the European Commission, National Standards Bodies (NSBs) and the national stakeholders who are their members, and European Stakeholder Organisations.

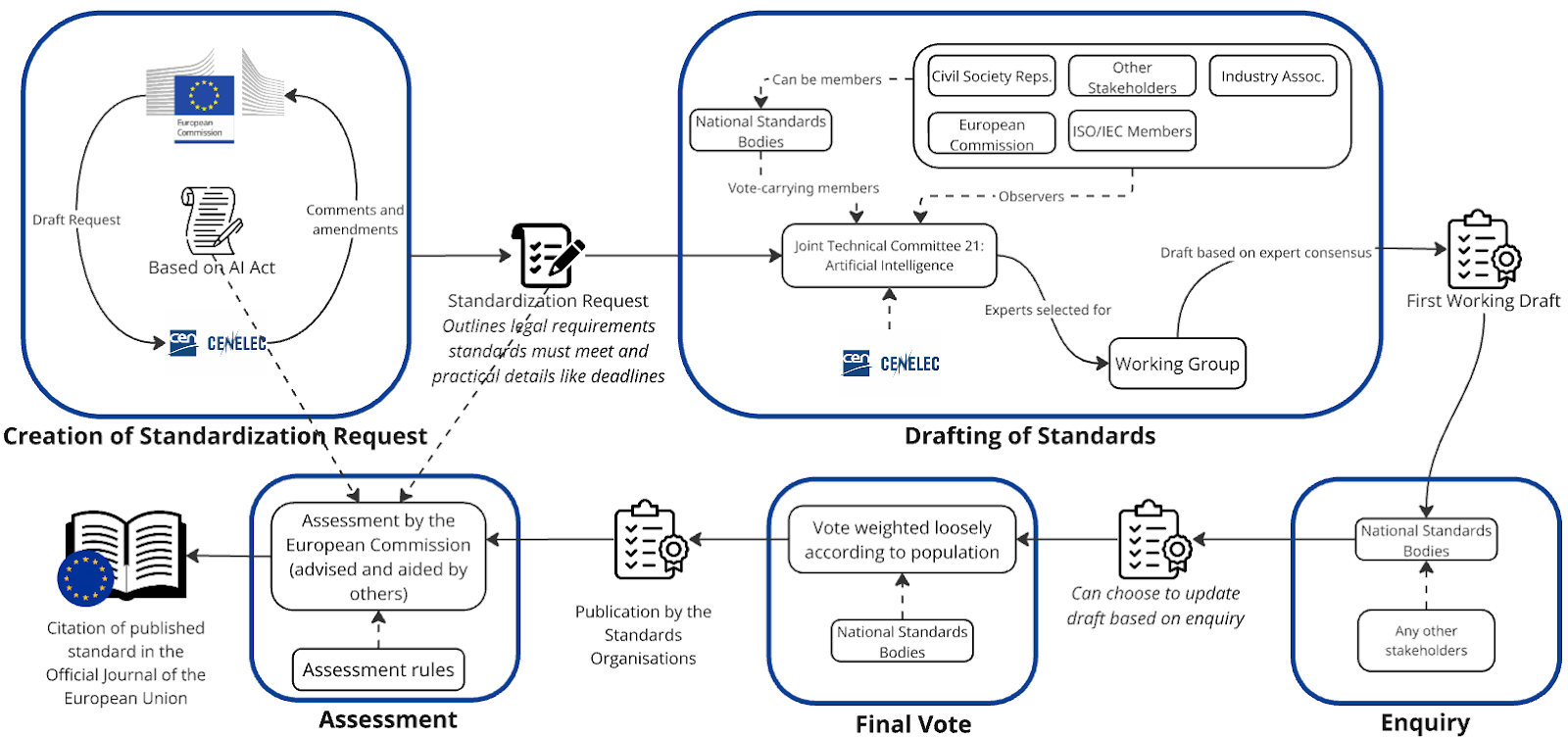

- There are six steps in the standardisation process: 1) a formal request by the Commission, 2) drafting by the ESOs, 3) enquiry, 4) formal vote by the ESO, 5) publication by the ESO, and 6) assessment and publication by the Commission. Different standards for the AI Act are in different stages of the process – you can find the publicly available work programme here.

- There are controversies about the functioning of the European standards system, and the European Commission is considering the need for reforms.

1. Background: EU AI Standards Process Details

The EU has a particular mechanism that envisages the writing of technical standards that become officially approved ‘manuals’ that describe how companies and other actors can comply with EU safety regulation. The central idea is that such standards, known as ‘harmonized and cited standards’ when approved, can provide a presumption of conformity of legal requirements. If a company demonstrates that their product or system complies with a harmonized and cited standard, market surveillance authorities and courts will presume that they comply with the corresponding legal requirement.

For the AI Act, the European Commission has requested an initial batch of such standards to be written for the AI Act and the writing is currently in process. This initial batch will cover the requirements for providers of high-risk AI systems. The Commission may request additional standards covering other parts of the AI Act in the future.

The EU standards request mechanism implies a division of labour. It allows the EU legislator to simply specify in the AI Act that certain safety related outcomes have to be achieved by AI model or system providers, and specify that generally acknowledged state-of-the-art methods of safety engineering shall be applied when achieving these outcomes. The text of the Act does not go into technical detail about what these state-of-the-art methods actually are. The expectation is that technical experts writing standards will fill in these details. The legislator further anticipates that these standards will be updated if the state of the art changes.

We should note at the outset that standards are not the only documents that can detail how to comply with the AI Act. For example, requirements for general-purpose AI providers are clarified in a Code of Practice writing effort. Furthermore, some AI Act requirements will be further clarified in guideline documents penned by the European Commission.

The use of standards as a means of compliance remains voluntary. Providers may ignore the harmonised standards, and rely on independently interpreting the legal text. For their interpretation they may rely on books, guides, web sites, or legal opinions written by independent authors or industry alliances. Such independent work does not have the officially approved status of standards, and will not give a presumption of conformity, but it may be available earlier or be more customised to a specific situation.

2. Key Actors

To understand the development of European standards for the AI Act, it is helpful to start off with an overview of the central actors in the process.

- The European Commission: It is composed of 27 Commissioners which are put forward by member states and approved by the European Parliament. It acts as the executive branch of the EU. The Commission is in charge of requesting and approving European standards from the European Standards Organisations.

- The European Standards Organisations (ESOs): There are three organisations that are responsible for all EU standard-setting: CEN, CENELEC, and ETSI. The former two are leading on the creation of AI Act standards through their joint committee with the name CEN/CENELEC JTC21. These bodies are independent of the EU institutions, including the Commission, and they can also create other standards by their own initiative. The ESOs are required to bring together different stakeholders, some of which are introduced below.

- National Standards Bodies (NSBs): These are responsible for standards in each of the Member States. See for example a list of all member NSBs in CEN. Each national body represents the interest of all stakeholders in the respective country: government, industry, and civil society by allowing national level parties to become members of their committees, typically requiring a participation fee. Such committees discuss and determine national votes and comments on draft standards. The committees can also appoint members as technical experts contributing to drafting inside ESO working groups. Such technical experts are bound by a code of conduct that requires them to ‘work for the net benefit of the European community1, which may require setting aside preferences of the national stakeholders paying their salary, travel costs, and participation fees.

- European Stakeholder Organisations: A variety of interests within the EU are represented in further organizations, for example those of Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs), trade unions, the environment, and consumers. Some of these are entitled to comment and participate without first becoming a member of a national body level committee, as well as some EU funding to participate, in accordance with Annex III of Regulation (EU) No 1025/2012.

- Harmonised Standards Consultants: For some standards drafting, private consultants are hired by the Commission to ensure that the standards developed by the ESOs are suitable for publication by the EU. However, for the AI Act, the Commission decided to perform the required suitability assessment itself. The role of harmonised standards consultants is described in more detail here.

3. Process Steps

The process for developing harmonised standards is complex. It starts with a standards request from the Commission, followed by drafting by the relevant ESO, enquiry, voting, and publication, before the final step of citation of the standards in the Official Journal of the European Union. Each step is explained below. For a more extensive overview, see the CEN website.

Step 1: The Commission Creates a Standardisation Request for the ESOs

Such a request includes details on which part of the corresponding legislation needs to be covered by the requested standards and a requested delivery date. A draft request is refined in consultation with ESOs and other stakeholders to be acceptable to all. Once approved by the Commission and representatives from EU governments, the request is published and ESOs must formally respond. While rejecting a request is possible, ESOs usually accept requests, even if they have doubts about the feasibility of completing the work by the requested delivery date. See Vademecum on European Standardisation for further details.

Step 2: The ESOs Draft the Standards

Standards are drafted in technical committees with technical experts from the NSBs. A committee also includes a selection of stakeholders as observers. As mentioned above, the technical committee for the AI Act is a joint committee between CEN and CENELEC called CEN/CENELEC JTC21. Working groups are formed within the committee, where technical experts draft the standards documents. These experts are all volunteers, in the sense that they are not compensated from CEN and CENELEC for their time and effort. Experts are bound by confidentiality rules, for example they cannot reveal details of ongoing discussions or the contents of in-progress working drafts. Unanimous expert agreement, or expert consensus if unanimity is not possible, is needed to pass drafts to the next process step.

Usually the European ESOs try to leverage, and not overrule, existing work in international standards written by ISO/IEC (the Organization for International Standardization and the International Electrotechnical Commission). This is to ensure international consistency and is an important part of the WTO’s Technical Barriers to Trade agreement, which prevents countries from using standards to block international trade.

Step 3: Enquiry

Enquiry is a voting and commenting step where a complete draft standard prepared by a working group is evaluated by national stakeholders. The NSBs collect and send feedback, which is sent back to the experts in the working group who may update the draft based on the feedback. It is not uncommon that different NSBs give conflicting comments, with one country wanting a change in one direction, another country wanting a different change. It is up to the experts in the working group to handle such conflicts by finding a compromise or plainly rejecting certain comments. Plain rejections run the risk that the country will vote ‘no’ in the next step, formal vote. Very negative feedback during enquiry could trigger a process reset, where large parts of the draft are entirely re-written, with the new version then being submitted to a second enquiry vote. A working group may also decide to resolve concerns by just omitting material that has proven to be very controversial. This may yield a standard that does not fully cover the topics requested in the Standardisation Request anymore.

Step 4: Formal Vote

In this process step, the NSBs formally vote to either accept or reject the standard into which their feedback has been incorporated in the previous step. A ‘no’ vote can trigger another round of drafting and re-submission to a new vote. A ‘yes’ vote can still be accompanied by comments, but these should only propose minor edits.

Step 5: Publication

Based on a successful vote, the standard is published by CEN and CENELEC. Published standards are typically available for purchase in web shops, though some are available for free. A recent case in front of the European Court of Justice addressed the appropriateness of ESOs charging money for standards that directly support EU Law. At the time of writing, it is unclear what effects these lawsuits will eventually have on the fee-based funding model of the ESOs.

Step 6: Assessment Followed by Citation in the Official Journal of the European Union

In the final step, the European Commission will carry out an assessment of whether the published standards correctly satisfy the conditions in the Standardisation Request and correspond to the text in the AI Act. However, the European Commission is also involved during the drafting process, providing feedback in the form of preliminary assessments of the drafts. After completing a successful assessment, the Commission can adopt an implementing act citing the standard in the Official Journal of the European Union (OJEU). This makes the standard a harmonized and cited standard that brings a “presumption of conformity” with the applicable parts of the law.

The Commission maintains a website listing all cited harmonised standards for specific regulated fields. In mature fields, there can be tens or hundreds of such standards, developed and updated over decades.

Simplified view of the standard setting process for the EU AI Act

AI Act Standard Setting Timeline Highlights

The timeline below is based on publicly known information as of June 2025.

| EU/European Commission | European Standards Organisations |

|---|---|

| 21 April 2021: Commission publishes first draft of the AI Act | |

| June 2021: CEN-CENELEC JTC21 has its first meeting to start work on the AI Act, in anticipation of getting a Standardisation Request eventually. | |

| 20 May 2022: Commission releases first draft standardisation request in support of safe and trustworthy AI. | |

| 22 May 2023: Commission adopts standardisation request C(2023)3215, accepted by CEN and CENELEC. Requested delivery date of the standards is 30 April 2025 Available here. | |

| 12 July 2024: The final version of the AI Act is published in the Official Journal of the European Union. | |

| Second half of 2024: Commission starts work on an amended standardisation request that references the final version of the AI Act. | August 2024: The JTC21 chair reports to the media that the requested standards are expected to be completed by the end of 2025, around eight months later than expected. |

| September 2024: JTC21 reports in its public newsletter edition 5 that it has reached the milestone where all of its projects in support of the Standards Request have passed the ‘approval’ stage and are in the ‘under drafting’ stage. | |

| ~November 2024:The JTC21 chair reports on linkedin that the aim is to finish the requested standards by late 2025 / early 2026. | |

| 15 April 2025: CEN-CENELEC flag delays to the media and reports that the work is likely to take up much of 2025 and partly 2026 for some deliverables. | |

| 30th April 2025: CEN-CENELEC JTC21 misses the expected delivery date from the standardization request C(2023)3215. Missing this delivery date has no automatic repercussions, the request remains in effect. | |

| 16 May 2025: According to media reports on a JTC21 internal timeline, the majority of the technical standards designed to facilitate compliance with the EU AI Act are now expected to be finalized shortly after the law’s legal requirements take effect, i.e. shortly after 2 August 2026. Furthermore, this batch is expected to only partially cover the AI law’s legal requirements. Full delivery covering all requested requirements is expected much later. | |

| 26 May 2025: MLex reports that the Commission is weighing a move to ‘stop the clock’ on enforcing some parts of the AI Act because of several developments, including expected delays in JTC21 finishing the standards. Stopping the clock would imply creating new legislation that moves several dates currently in the AI Act backwards. This could include the August 2026 and 2027 dates below. | |

| June 2025: in an EU ministerial report, Poland proposes to pause enforcement of the AI Act. The Commission formally acknowledges on June 6 that it does not rule out postponing parts of the AI Act in the forthcoming digital omnibus package. | |

| June 2025: The Commission adopts standardisation request C(2023)3215 with a delivery date on 31 August 2025. It has the same scope of standards, deliverables requested and technical standards as in request C(2025)3871. | |

| Ongoing: CEN and CENELEC Joint Technical Committee 21 is drafting the requested standards. Public live tracking of the work programme is available here. As reported in edition 5 of the public newsletter, this ‘live’ dashboard comes out of the CEN-CENELEC project tracking system, which is updated at irregular intervals. Future dates mentioned on the page may not correspond to the latest (confidential) plans maintained by the JTC21 committee itself. | |

| 2 August 2026: Requirements for article 6(2) of high-risk AI systems, requirements to be clarified by the JTC21 standards requested in C(2023)3215, come into force. | |

| 2 August 2027: Requirements for an additional class of article 6(1) of high-risk AI systems, to be clarified by the same JTC21 standards, come into force. |

5. Examples of How Standards Can Clarify the AI Act

To understand how standards could clarify the text of the AI Act, let us look at Articles 9 and 8(1) of the AI Act as examples.

Article 9 of the AI Act requires that a high-risk AI system is equipped with ‘risk management measures’ so that ‘relevant residual risk associated with each hazard, as well as the overall residual risk of the high-risk AI systems is judged to be acceptable’. Article 8(1) further specifies that this judgment must be made while taking into account ‘the generally acknowledged state of the art on AI and AI-related technologies’.

As a manual on how to fulfill these obligations, a standard could:

- Specify what ‘acceptable’ means: acceptable to whom?

- Detail how to make a judgement of acceptability of the remaining risk. For example, this could involve a cross-disciplinary team of experts who know both the application area, societal expectations around it, and the state of the art of AI technology.

- Outline what the state of the art says about if and when a stakeholder consultation process is appropriate to determine that risks are acceptable, and the design of such stakeholder consultations.

- Detail techniques that are appropriate to estimate residual risks in given situations

- Present checklists that enumerate specific risks, hazards, or considerations that are expected to be known to practitioners of the state of the art.

In mature and narrow fields like food safety or electrical engineering, the subject matter experts are often able to determine lab-tested and time-tested numerical thresholds for safe outcomes. For example, in the area of food safety, they may define that the risk of lead poisoning from a food of type A is at an acceptable level if a lab test on a representative sample shows that the lead content is below B parts per million. It is then for non-experts to use the safety standards and ensure safe outcomes according to the state of the art.

In contrast, it is unlikely that the experts working on the high-risk AI standards under the AI Act will be able to come up with similar numeric prescriptions. The field of AI covered by the AI Act is simply too diverse, and unlike in food-safety, it cannot fall back on long-lasting experience with product types that have been in the market for decades or centuries. Thus, the state-of-the art processes defined in the AI safety standards will likely require the involvement of expertise and expert judgement in order to be run correctly.

6. Concerns and Controversies

6.1. Timing Concerns and Mitigations

According to the AI Act, the legal requirements on a first category of high-risk AI systems go into force in October 2026. Ideally, corresponding standards would be available by October 2025 to allow providers sufficient preparation time. However, as is clear from the timeline overview above, these standards are unlikely to be completed by then.

Historically, ESOs have often had difficulties delivering the requested standards on time, even when making an early start, for example relating to the update to the Medical Device Regulation and the Radio Equipment Directive.

Article 41 of the AI Act anticipates potential delays in the development of standards. It allows the European Commission to establish “common specifications,” which would act as official interim guidance until the relevant standards are formally approved. As of the time this post was last updated, the Commission has not publicly indicated any intention to utilise this provision. As shown in the timeline above, the Commission has however indicated that the option of postponing the entry into force of the high-risk requirements, to a date beyond October 2026, could be considered.

6.2. Concerns About Democratically Valid Outcomes

The standards process, and the checks and balances inside and around it, have been designed with the intent to create trusted and democratic outcomes. However, the standards development process has been subject to critique on several points. This includes critique that the process happens behind closed doors without transparency. It has also been criticised for having gameable design features which in practice lead to well-resourced technology companies dominating the process and bad faith actors high-jacking the process. Some have also questioned whether the current process is fit for purpose to deliver law-clarifying standards for digital technologies as part of the EU’s digital agenda. This concern is particularly relevant to AI standards development, given the complex and sometimes controversial nature of AI technology.

6.3. Potential Reform of the European Standards System

The European Commission announced in 2022 that it would take actions to ‘improve the governance and integrity of the European standardisation system’. At this time of writing this improvement initiative is still ongoing. As part of this initiative, the Commission has collected input via open calls in 2023 and 2024. The 2024 written inputs have not been published in detail, but the 2023 written inputs can all be read here. These inputs show extensive diversity in opinions between stakeholders. Some stakeholders report that the EU standardisation system is working well, and see no need for significant updates, while others report that it is not working well at all, and that significant reforms are needed.

Among this second group, a common theme is the need to ensure greater participation from non-industry players, such as independent academic experts. The need for more funding to support such players and removing other barriers to participation is often mentioned. An important feature of the current process is that, while it is open to participation by representatives and experts from a very broad range of stakeholders, by default none of these representatives or experts get paid for their work, or reimbursed for associated travel costs. While there are some limited funding sources to support participants from academia, small medium enterprises, and civil society organisations, many stakeholders feel that much more funding would be needed, in order to overcome the problem of including more stakeholders and experts. Reasons for including more parties would be to create more (trust in) democratically balanced outcomes, and to ensure that there is enough expertise and workforce in the committee to finish the standards writing process within reasonable time.

7. Further Reading

Official information on JTC21:

- The ‘Joint Technical Committee 21: Artificial Intelligence’ page is here.

- The JTC21 outreach website is here.

- JTC21 also publishes newsletters that report on, and raise awareness of, its standardization activities.

- Some additional information on the JTC21 work programme (also covering standards not related to the Standardisation Request, and the writing of some technical reports) is here.

On how standardisation works in the EU and AI Act context:

- Regulation (EU) No 1025/2012, available here, has a full description of EU standardisation.

- The CEN-CENELEC internal regulations governing standards work are available here.

- For AI Act specific coverage, see also this paper from 2021 and this report from 2024.

Research papers and reports on various aspects of AI Act standards development, some of these include insights based on interviewing experts working in JTC21:

- Christine Galvagna Inclusive AI governance, Civil society participation in standards development. 2023. See also here for a summary of an event discussing this paper.

- Mélanie Gornet, Hélène Herman. A peek into European standards making for AI: between geopolitical and economic interests. 2024. hal-04784035

- Mélanie Gornet. Too broad to handle: can we ”fix” harmonised standards on artificial intelligence by focusing on vertical sectors?. 2024. hal-04785208

Notes and References

- Note that ‘European community’ is not the same as the European union, but refers to all countries who are CEN and CENELEC members. This for example includes the UK. ↩︎