In their recent publication on robust European AI governance, Claudio Novelli, Philipp Hacker, Jessica Morley, Jarle Trondal, and Luciano Floridi pursue two main objectives: explaining the governance framework of the AI Act and providing recommendations to ensure its uniform and coordinated execution (Novelli et al., 2024).

The following provides a selective overview of the publication, with a particular focus on the AI Office and GPAI. It is important to note that this overview refrains from introducing new perspectives, but focuses solely on reiterating the most relevant findings of the publication for clarity and accessibility for policymakers.

The original publication is available at SSRN via the SSRN link, or DOI link.

1. Implementing and enforcing the AI Act: the remaining steps for the Commission

| Key aspects | Tasks and responsibilities of the Commission |

|---|---|

| a) Procedures | • Establish and work with the AI Office and AI Board to develop implementing and delegated acts • Conduct the comitology procedure with Member States for adopting and implementing acts • Manage delegated act adoption, consulting experts and undergoing scrutiny by EP and Council |

| b) Guidelines | • Issue guidelines on applying the definition of an AI system and classification rules for high-risk systems • Create risk assessment methods for identifying and mitigating risks • Define rules for “significant modifications” that alter the risk level of a high-risk system |

| c) Classification | • Update Annex III to add or remove high-risk AI system use cases through delegated acts • Classify GPAI as exhibiting “systemic risk” based on criteria like FLOPs and high-impact capabilities • Adjust regulatory parameters (thresholds, benchmarks) for GPAI classification through delegated acts |

| d) Prohibited Systems | • Develop guidelines on AI practices that are prohibited under Article 5 (AIA) • Set standards and best practices to counter manipulative techniques and hazards • Define criteria for exceptions to prohibitions, e.g., for law enforcement use of real-time remote biometric identification |

| e) Harmonized standards and high-risk obligations | • Define harmonized standards and obligations for highrisk system providers, including in-door risk management system (Article 9 AIA) • Standardize technical documentation requirements and update Annex IV via delegated acts as necessary • Approve codes of practice (Article 56(6) AIA) |

| f) Information and Transparency | • Set information obligations for providers of high-risk systems throughout the AI value chain • Issue guidance to ensure compliance with transparency requirements, especially for GPAI |

| g) Enforcement | • Clarify the interplay between the AIA and other EU legislative frameworks • Regulate regulatory sandboxes and supervisory functions • Oversee Member State’’ setting of penalties and enforcement measures that are effective, proportionate, and deterrent |

1.1 Guidelines for risk-based classification of AI

- Within the framework of risk assessments, the Commission is yet to define rules about “significant modifications” that alter the risk level of a system once it has been introduced to the market (Art 43(4) AIA). Novelli et al. expect that standard fine-tuning of foundation models should not lead to a substantial modification, unless the process explicitly involves removal of safety layers or other actions that clearly increase risk.

- A complementary approach to risk assessment that Novelli et al. offer is to adopt predetermined change management plans akin to those in medicine; these are documents outlining anticipated modifications (e.g. performance adjustments, shift in intended use) and methods for assessing such changes.

1.2 Classification of general-purpose AI (GPAI)

- The Commission has notable authority under the AIA to classify GPAI as exhibiting ‘systemic risk’ (Art 51 AIA). Novelli et al. consider this distinction crucial: only systemically risky GPAIs are subject to the more far-fetching AI safety obligations concerning evaluation and red teaming, comprehensive risk assessment and mitigation, incident reporting, and cybersecurity (Art 55 AIA). The Commission can initiate the decision to classify a GPAI as systemically risky, or do so in response to an alert from the Scientific Panel.

- The Commission is able to dynamically adjust regulatory parameters. Novelli et al. find this essential for a robust governance model, in particular because the trend in AI development moves towards creating more powerful, yet “smaller” models (that require fewer FLOPs).

- Art 52 outlines how GPAI providers may contest the Commission’s risk classification decisions. Novelli et al. foresee this potentially becoming a primary area of contention within the AI Act. GPAI providers whose models are trained with fewer than 10^25 FLOPs, yet esteemed systemically risky by the Commission, are expected to contest, possibly reaching the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). This allows providers with deep pockets to delay the application of the more stringent rules. Simultaneously, this reinforces the importance of the rapidly outdating 10^25 FLOP threshold for GPAI.

1.3 Enforcement timeline: grace period and exemptions

- Existing GPAI systems already on the market are granted a grace period of 24 months before they must fully comply with the AIA (Art 83(3) AIA). Novelli et al. note that, more importantly, high-risk systems already on the market for 24 months after the entry into force are entirely exempt from the AIA until ‘significant changes’ (defined in section 3.2) are made in their designs (Art 83(2) AIA). They contend that this is arguably in deep tension with a principle of product safety law: it applies to all models on the market, irrespective of when they entered the market. Moreover, the grace period for GPAI and the exemption for existing high-risk systems favor incumbents over newcomers, which is questionable from a competition perspective.

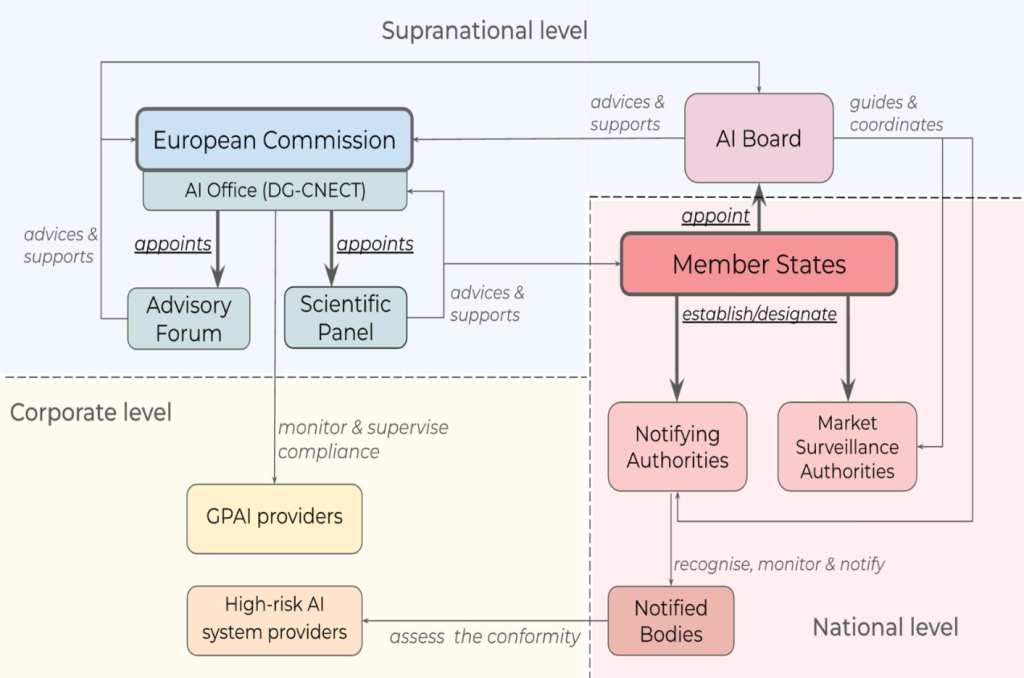

3. Supranational authorities: the AI Office, the AI board, and the other bodies

| Institutional Body & Structure | Mission and Tasks |

|---|---|

| AI Office (Art 64 AIA and Commission’s Decision) Centralized within the DG-CNECT of the Commission | • Harmonise AIA implementation and enforcement across the EU • Support implementing and delegated acts • Standardization and best practices • Assist in the establishment and operation of regulatory sandboxes • Assess and monitor GPAIs and aid investigations into rule violations • Provide administrative support to other bodies (Board, Advisory Forum, Scientific Panel) • Consult and cooperate with stakeholders • Cooperate with other relevant DG and services of the Commission – International cooperation |

| AI Board (Art 65 AIA) Representatives from each Member State, with the AI Office and the European Data Protection Supervisor participating as observers | • Facilitate consistent and effective application of the AIA • Coordinate national competent authorities • Harmonise administrative practices. • Issue recommendations and opinions (upon requests of the Commission) • Support the establishment and operation of regulatory sandboxes • Gather feedback on GPAI-related alerts |

| Advisory Forum (Art 67 AIA) Stakeholders appointed by the Commission | • Provide technical expertise • Prepare opinions and recommendations (upon request of the Board and the Commission) • Establish sub-groups for examining specific questions • Prepare an annual report on activities |

| Scientific Panel (Art 68 AIA) Independent experts selected by the Commission | • Support enforcement of AI regulation, especially for GPAI • Provide advice on the classification of AI models with systemic risk • Alert AI Office of systemic risks • Develop evaluation tools and methodologies for GPAIs • Support market surveillance authorities and cross-border activities |

| Notifying Authorities (Artt 28–29 AIA) Designated or established by Member States | • Process applications for notification from conformity assessment bodies (CABs) • Monitor CABs • Cooperate with authorities from other Member States • Ensure no conflict of interest with conformity assessment bodies • Conflict of interest prevention and assessment impartiality |

| Notified Bodies (Artt 29–38 AIA) A third-party conformity assessment body (with legal personality) notified under the AIA | • Verify the conformity of highrisk AI systems • Issue certifications • Manage and document subcontracting arrangements • Periodic assessment activities (audits) • Participate in coordination activities and European standardization |

| Market Surveillance Authorities (Artt 70–72 AIA) Entities designated or established by Member States as single points of contact | • Non-compliance investigation and correction for high-risk AI systems (e.g., risk measures) • Real-world testing oversight and serious incident report management • Guide and advice on the implementation of the regulation, particularly to SMEs and start-ups • Consumer protection and fair competition support |

3.1 The AI Office

1. Institutional composition and operational autonomy

- Novelli et al. note that the Office’s precise organizational structure and operational autonomy remain ambiguous. No provisions, either in the AIA or in the Commission’s decision, have been established regarding the composition of the AI Office, its collaborative dynamics with the various Connects within the DG, or the extent of its operational autonomy. Novelli et al. hypothesize that this absence is likely justified by the expectation that the Office will partially use existing infrastructure of DG-CNECT. Nevertheless, Novelli et al. underscore that expert hiring and substantial funding will present significant challenges, as the Office will compete with some of the best-funded private companies on the planet.

- Regarding its operational autonomy, the Office’s incorporation in DG-CNECT means that the DG’s management plan will guide the AI Office’s strategic priorities. Novelli et al. note that this integration directly influences the scope and direction of the AI Office’s initiatives.

2. Mission(s) and task

- The primary mission of the AI Office, according to the Commission Decision, is to ensure the harmonized implementation and enforcement of AIA (Art 2, point 1 of the Decision). The Decision also outlines auxiliary missions, such as enhancing a strategic EU approach to global AI “initiatives”, promoting actions that maximize AI’s social and economic benefits, supporting AI systems that boost EU competitiveness, and keeping track of AI market advancements.

- Novelli et al. consider this very broad wording, one interpretation they propose is that the AI Office’s role could go beyond the scope of the AIA to include additional AI normative frameworks (such as the revised Product Liability Directive or the Artificial Intelligence Liability Directive (AILD)). In this case, Novelli et al. observe that the Office might need restructuring into a more autonomous body, like the CERT-EU, which could necessitate detaching it from the Commission’s administrative framework.

- The ambiguity in the current normative framework regarding breath and scope of the AI Office is considered a crucial aspect by Novelli et al. They consider the responsibilities assigned to the AI Office to be broadly defined, with the expectation that their precise implementation will evolve based on practical experience.

- An important aspect to consider within the operational scope of the Office is the nature of its decisions. Novelli et al. note that the AI Office does not issue binding decisions on its own, but supports and advises the Commission. They raise concern that the effectiveness of mechanisms for appealing decisions of the Commission may be compromised by the opaque nature of the AI Office’s support to the Commission, its interactions within DG-CNECT, and its relationships with external bodies, such as national authorities. Novelli et al. find this issue particularly pertinent given the AI Office’s engagement with external experts and stakeholders. They emphasize that documentation and disclosure of the AI Office’s contributions become crucial.

3.2 The AI Board, the Advisory Forum, and the Scientific Panel

1. Structures, roles and compositions of the three bodies

- For Novelli et al., having three separate entities with relatively similar compositions raises questions. The AI Board is understandable for ensuring representation and maintaining some independence from EU institutions. But why there is both an Advisory Forum and a Scientific Panel is not apparent. The Forum is intended for diverse perspectives of civil society and industry, essentially acting as an institutionalized form of lobbying while balancing commercial and non-commercial interests. In contrast, the Panel consists of independent and (hopefully) unbiased experts, with specific tasks related to GPAI.

2. Mission(s) and tasks

- Novelli et al. note that the Board does not have the authority to revise decisions of national supervisory agencies. They believe this may prove a distinct disadvantage, hindering the uniform application of the law if certain Member States interpret the AIA in highly idiosyncratic fashions. For instance, one may particularly think of the supervision of the limitations on surveillance tools using remote biometric identification.

- Novelli et al. consider the distinction between the Advisory Forum and the Scientific Panel less clear than the separation between the Board and the Office. They raise questions regarding the exclusivity of the Forum’s support to the Board and the Commission, given that the Panel exclusively supports the AI Office directly, and whether the Panel’s specialized GPAI expertise could benefit these entities. The participation of the AI Office in Board meetings is an indirect channel for the Panel’s expertise to influence broader discussions, but Novelli et al. consider this arrangement not entirely satisfactory. The Panel’s specialized opinion may become less impactful, since the AI Office lacks voting power in the Board meetings.

4. Recommendations for robust governance of the AI Act

Building on their analysis, Novelli et al. envision the following important updates that should be made to the governance structure of the AI Act.

4.1 Clarifying the institutional design of the AI Office

- Given the broad spectrum of tasks anticipated for the AI Office, more detailed organizational guidance is needed. Additionally, the Office’s mandate lacks specificity concerning the criteria for selecting experts that are to carry out evaluations (Recital 164 AIA).

- Integrating the AI Office within the framework of the Commission may obscure its operational transparency, given the obligation to adhere to the Commission’s general policies on communication and confidentiality. For example, the right for public access to Commission documents (Regulation (EC) No 1049/2001) includes numerous exceptions that could impede the release of documents related to the AI Office. Novelli et al. give the exception of documents that would compromise “[…] commercial interests of a natural or legal person, including intellectual property,” a broadly defined provision lacking specific, enforceable limits. A narrower interpretation of these exceptions could be applied to the AI Office to help circumvent transparency issues.

- Further clarification regarding the AI Office’s operational autonomy is required. Novelli et al. propose that this could come in the form of guidelines for decision-making authority, financial independence, and engagement capabilities with external parties.

- An alternative, potentially more effective approach would be establishing the AI Office as a decentralized agency with its legal identity, like EFSA and the EMA. This model would endow the AI Office with enhanced autonomy, including relative freedom from the political agendas at the Commission level, a defined mission, executive powers, and the authority to issue binding decisions. Novelli et al. observe some risk of agency drift, but state that empirical evidence suggests that the main interlocutors of EU agencies are “parent” Commission DGs.

4.2 Integrating the Forum and the Panel into a single body

- Novelli et al. argue that consolidating the Forum and the Panel into a singular entity would reduce duplications and strengthen the deliberation process before reaching a decision. This combined entity would merge the knowledge bases of civil society, the business sector, and the academic community, which Novelli et al. expect to promote inclusive and reflective discussions of the needs identified by the Commission. They conclude that this approach could significantly improve the quality of advice to the Board, the Office, and the other EU institutions or agencies.

- Should merging the Forum and the Panel prove infeasible, an alternative solution could be to better coordinate their operations, through clear separations of scopes, roles, tasks, but unified reporting. Novelli et al. suggest producing a joint annual report consolidating contributions from the Forum and the Panel, cutting administrative overlap and ensuring a more unified voice to the Commission, Board, and Member States.

- Merging or enhancing coordination between the Forum and the Panel favors robust governance of the AIA by streamlining advisory roles for agility and innovation, also in response to disruptive technological changes.

4.3 Coordinating overlapping EU entities: the case for an AI Coordination Hub

- As AI technologies proliferate across the EU, collaboration among regulatory entities becomes increasingly critical, especially when introducing new AI applications intersects with conflicting interests. A case in point is the decision by Italy’s data protection authority to suspend ChatGPT. Novelli et al. consider it crucial to incorporate efficient coordination mechanisms within the EU’s legislative framework.

- Furthermore, they see the establishment of a centralized platform, the European Union Artificial Intelligence Coordination Hub (EU AICH), emerging as a compelling alternative. Novelli et al. argue that establishing such a hub will elevate the uniformity of AIA enforcement significantly, while improving operational efficiency and reducing inconsistencies in treating similar matters.

4.4 Control of AI misuse at the EU level

- The absence of authority for the AI Board to revise or address national authorities’ decisions, presents a notable gap in ensuring consistent AI regulations. This is concerning, especially regarding the AIA’s restrictions on surveillance tools, including facial recognition technologies.

- Without the ability to correct or harmonize national decisions, there’s a heightened risk that AI could be misused in some Member States, potentially facilitating the establishment of illiberal surveillance regimes, and stifling legitimate dissent. Novelli et al. underscore the need for a mechanism within the AI Board to ensure uniform law enforcement and prevent AI’s abusive applications, especially in sensitive areas like biometric surveillance.

4.5 Learning mechanisms

- Given their capacity for more rapid development and adjustment, Novelli et al. see the agility of nonlegislative acts as an opportunity for responsive governance in AI. However, they note that the agility of the regulatory framework must be matched to the regulatory bodies’ adaptability. Inter- and intra-agency learning and collaboration mechanisms are essential for addressing AI’s multifaceted technical and societal challenges. They suggest that specific ex-ante and ex-post review obligations could be introduced.

- More importantly, Novelli et al. propose that a dedicated unit, for example, within the AI Office should be tasked with identifying best and worst practices across all involved entities (from the Office to the Forum). Liaising with Member State competence centers, such a unit could become a hub for institutional and individual learning and refinement of AI, within and beyond the scope of the AIA framework.

References

Novelli, Claudio and Hacker, Philipp and Morley, Jessica and Trondal, Jarle and Floridi, Luciano, A Robust Governance for the AI Act: AI Office, AI Board, Scientific Panel, and National Authorities (May 5, 2024). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4817755 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4817755